The Machinists Union—and the North American labor movement—had a larger role in taking down the institutional racism of South African apartheid than you may have thought.

Twenty-three years ago, on April 27, 1994, South Africa held its first national election in which non-whites were allowed to vote. The people elected Nelson Mandela, a civil rights icon who the apartheid government had jailed for rallying the majority-black country against apartheid.

In South Africa, April 27 is now known as Freedom Day.

IAM General Vice President George Poulin was in South Africa just two days before the historic vote to investigate a Crown, Cork & Seal plant where workers had been on strike for over a year. The IAM represents U.S. workers at the company.

After visiting the plant, South African trade unionists took Poulin to an election rally in Cape Town. He wasn’t expecting to speak, until he was called to address a pro-apartheid crowd of 700 people.

“It sort of propelled me into what was a serious thing that was happening in that country,” Poulin said in an oral history conducted by the Southern Labor Archives.

He told the crowd a vote for Mandela is a vote for working people of all colors.

“If only two people in a hall of 700 went to vote the right way, I think it was a contribution,” said Poulin.

The IAM, and representatives of the AFL-CIO, were in South Africa on election day to watch for voter fraud, Poulin said.

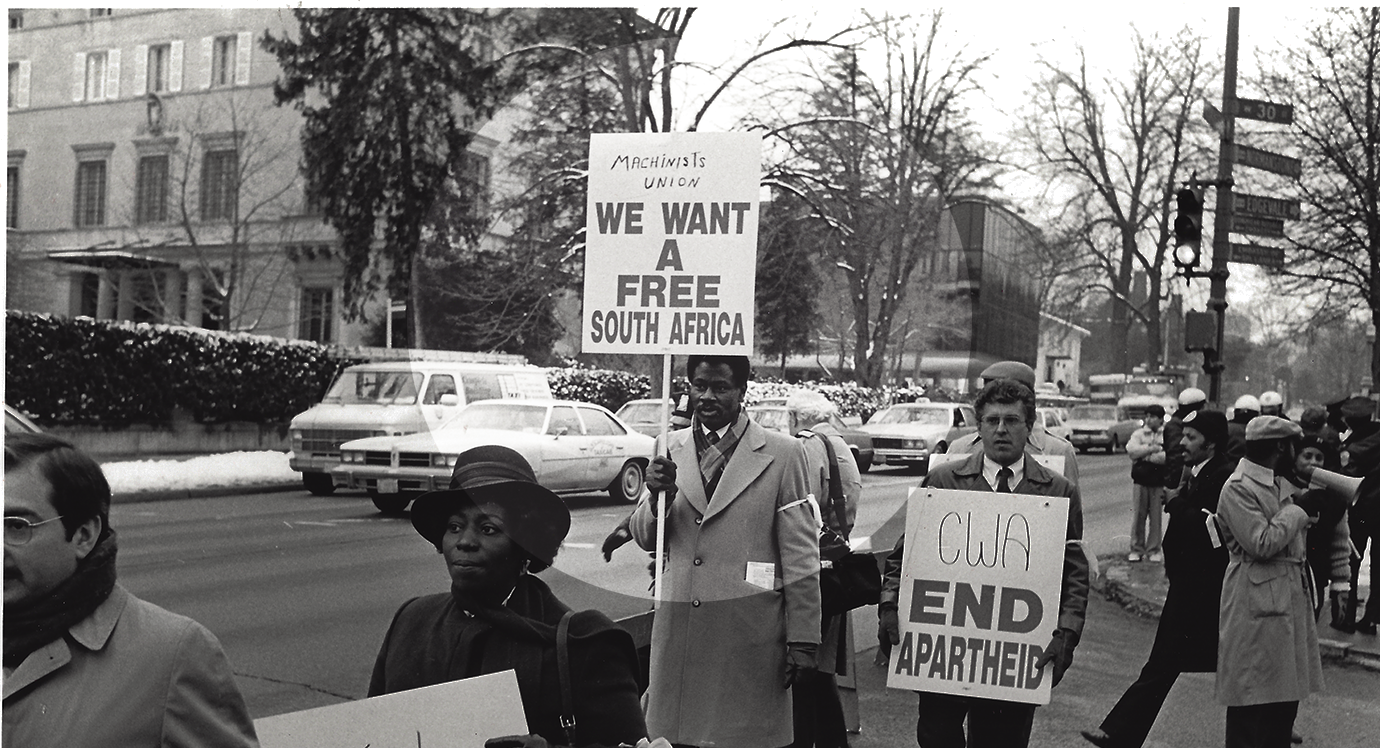

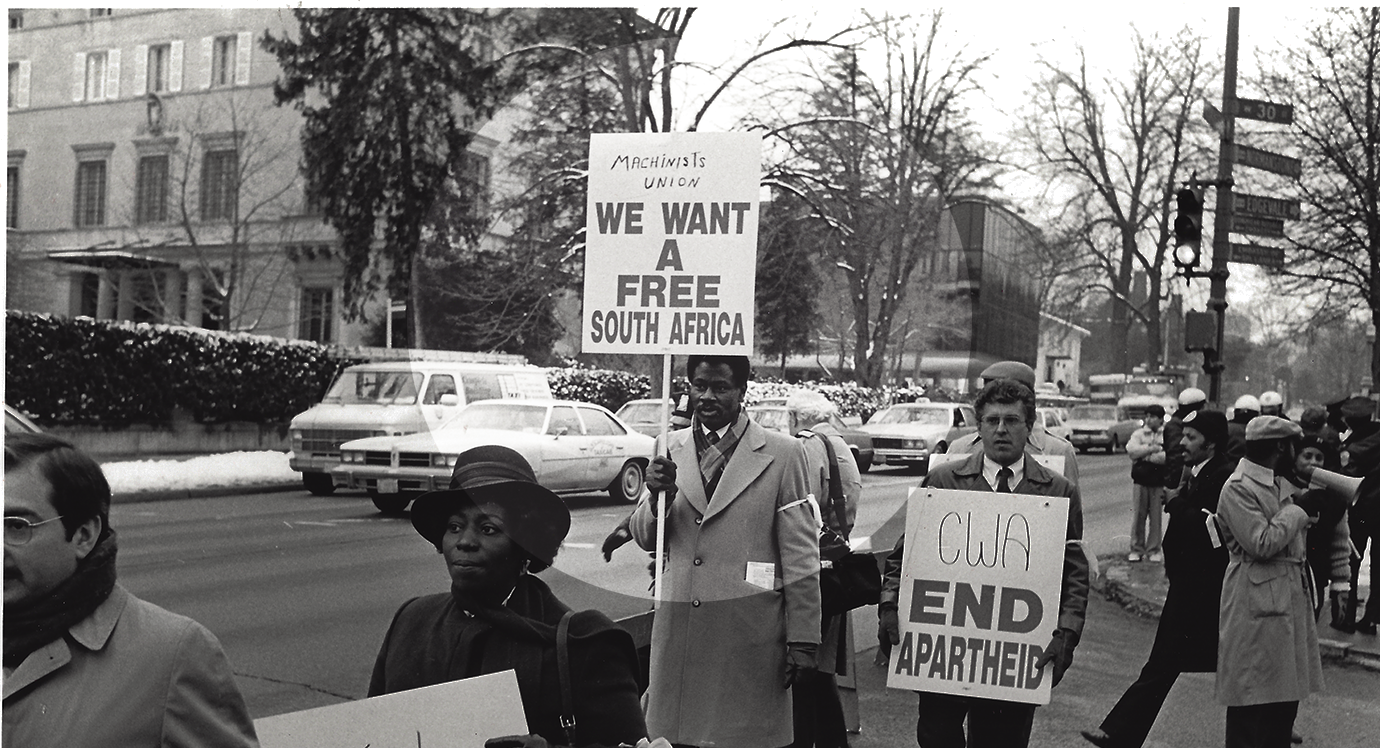

But the Machinists Union’s fight against apartheid goes back further than South Africa’s first free election. It joined other North American unions in calling for “selective disinvestment” from multi-national corporations whose operations bolstered the racist apartheid system, a 1985 edition of The Machinist reported.

Former IAM International Affairs Director Ben Sharman found himself staring apartheid in the face on a 1986 trip to meet with South African metal workers’ unions. He was invited to the funeral of a South African labor leader who had been killed by the apartheid police force.

The South African unionists were hoping Sharman’s presence would discourage a police raid on the gathering. On their way to the funeral, which was being held in a black township, Sharman was stopped by police.

They issued him a summons, written in Afrikaans, to get out within five minutes.

“It was written in a language I didn’t understand,” said Sharman. “But I did understand the machine guns.”

Under apartheid, South African police were allowed to detain people for at least 14 days without cause.

“Fourteen days is just enough time to let the wounds heal that were inflicted upon the arrest—enough time to get rid of the evidence of police abuse and torture,” Sharman told The Machinist.

Amnesty International reported more than 7,800 people were detained by apartheid police that year, and in a span of 18 months, more than 1,000 South Africans had been killed by police.

Trade unionists were among the most targeted groups. Organized labor, one of the country’s few racially mixed institutions, threatened a system that paid black workers an average of $5 per hour less than their white counterparts in the same plant.

“We must not let the multinationals force U.S. workers down to the South African standard of living,” said Sherman. “And we certainly cannot stand by while our brothers and sisters are brutally beaten for pursuing the ideals of the trade union movement.”

South African labor unions, and international allies such as the IAM, would become a key bloc in a growing movement that eventually took down apartheid. Only 20,000 South Africans were union members in 1970. By 1985, that number had grown to more than one million.

They began taking up issues such as women’s rights, health and safety and the right to negotiate on behalf of their members. A two-day strike in 1984 shut down a major South African industrial center. The IAM offered its advice and assistance throughout the struggle.

Today, the South African labor movement continues to assert its influence. The country’s largest union federation recently pulled support for President Jacob Zuma, who they say has abandoned the goals of working people in favor of the enrichment of political allies.

The IAM remains in close contact with South African labor unions.

“I did feel a little satisfaction… knowing I was part of history,” said Poulin, “even a very minute part of history.”